White Box Testing: Test All Paths

Since the code under test is known, the code may be used to guide writing unit or integration tests for a method. One testing strategy is to ensure that every path in the method has been executed at least once. We can determine all of the valid paths, called the basis set, through a method and write a test for each one. Using equivalence classes to drive white box testing should identify most of the possible paths through a method. Supplementing equivalence class testing with information about the possible paths ensures that all statements in the method are executed at least once and increases confidence that the method works correctly.

When performing white-box testing we are interested in the control flow

of the program. The control flow is a graph that contains decision

points and executed statements. Each decision (conditional test in an if

statement) in the method is shown as a diamond. The statements are in

rectangles.

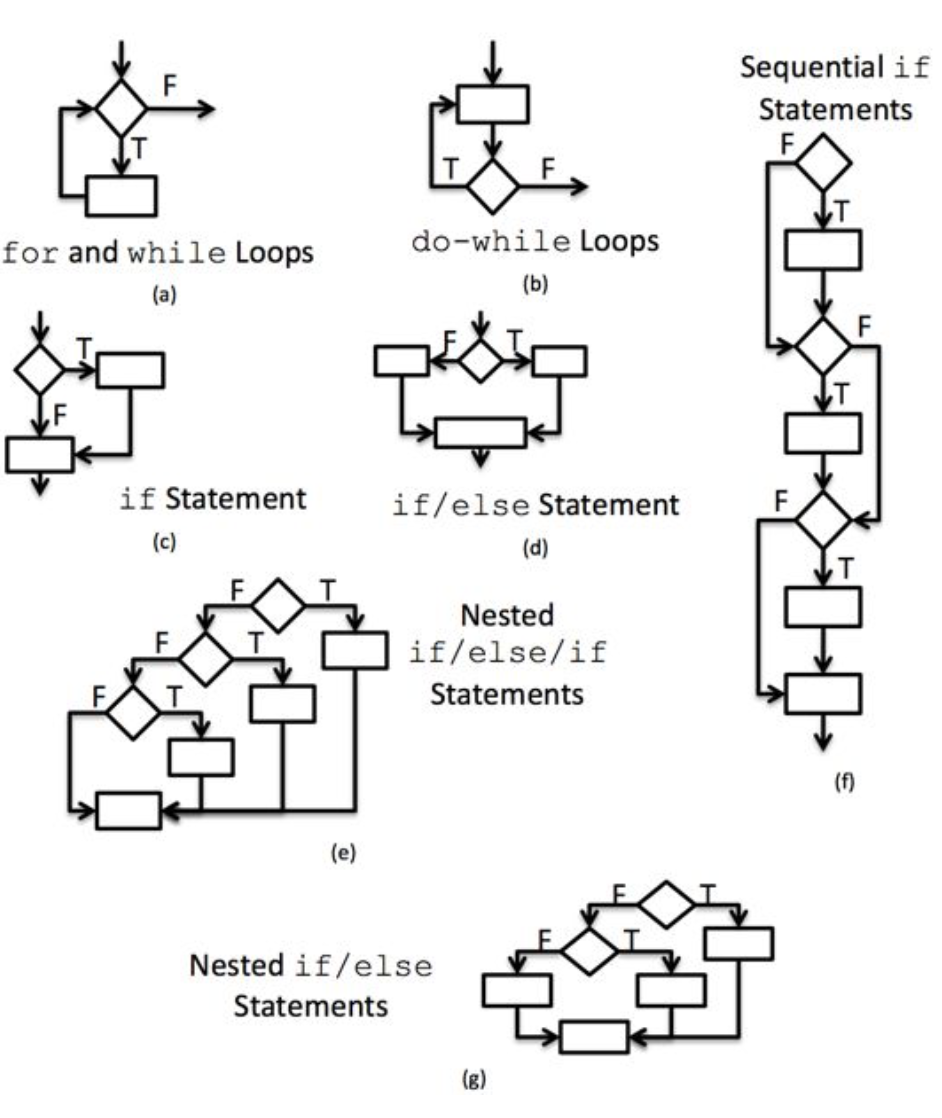

There are standard templates for each of the control structures that make decisions in our code. These templates are provided in Figure 9, a-g.

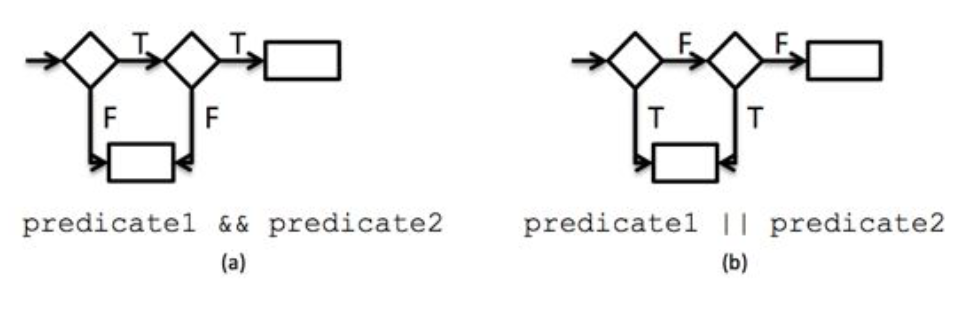

If the if statement contains compound conditional tests (i.e., the

conditional tests are separated by && or ||), then each conditional test

within the compound statement is shown as a separate diamond. Figure

10a-b shows standard templates for conditional statements with compound

predicates. Figure 10a shows two predicates that are and-ed together.

Both statements have to true for the statement on the right to execute.

If either predicate is false, then the inner portion of the conditional

test will never execute. Figure 10b shows two predicates that are or-ed

together. Either statement can be true for the body of the conditional

(represented by the lower statement) to execute. If both statements are

false, then the body of the conditional test never executes.

A measure called cyclomatic complexity provides a guide for the number of possible paths through the code. When creating white box tests, we want to create a test case for each possible path through the code. There are several calculations for cyclomatic complexity, but the easiest is to add one to the number of decision nodes (diamonds) in the control flow graph. Cyclomatic complexity provides us with the upper bound of the number of tests that we should write to guarantee full execution of the method if the tests are chosen appropriately such that they cover the paths. That is the minimum set of test cases that we should write just for execution of all conditionals on their true and false paths. However, one or more of the paths may be invalid. If a program requires that the same conditional predicate is used in two sequential if statements, that predicate will always evaluate the same as long as there is no change to the value. The path where one predicate would first evaluate true and the second predicate would evaluate to false can never occur. That’s why cyclomatic complexity is an estimate of the number of tests that you need for a method.

Once we have possible paths, we can create input values that will test each of the paths. Creating tests to consider all paths of statements is straightforward. Creating tests to consider all paths of loops is more complex. We could create many more paths that would execute the loop more than once, leading to a potentially infinite number of test cases. There is typically not enough time to run all possible test cases, so only focus on the paths through the code where a loop is run once through its body.

Pressman1 provides the following guidance for testing a simple loop

(i.e., no nesting), where the loop is expected to iterate n times.

- Fail the conditional test for entering the loop, so that the loop never executes;

- Execute the body of the loop only once;

- Execute the body of the loop twice;

- Execute the body of the loop

mtimes, wherem < n; - Execute the body of the loop

n – 1times; - Execute the body of the loop

ntimes; and - Execute the body of the loop

n + 1times.

A loop’s execution ranges from the lower boundary to n. The first set

of three test cases test the loop’s lower boundary value. The 4th test

case is a representative equivalence class test of the loop’s input

range. The last 3 test cases test loop’s upper boundary value. Some of

the tests may lead to redundancies if the loop’s bounds are dependent on

the input, so create as many distinct tests as possible, ensuring at a

minimum coverage of all paths through the loop.

Nested loops introduce additional complexity when testing. Pressman1 gives the following guidance for testing nested loops:

- Keeping all outer loops to minimal values that reduce the number of iterations, test the innermost loop using the techniques listed above.

- Move up the level of nested loops, and test the loop using the techniques listed above. The outer loops should kept to minimal iterations and any inner loops should be iterated a “typical” number of times.

- Continue moving up the level of nested loops until all loops are tested.

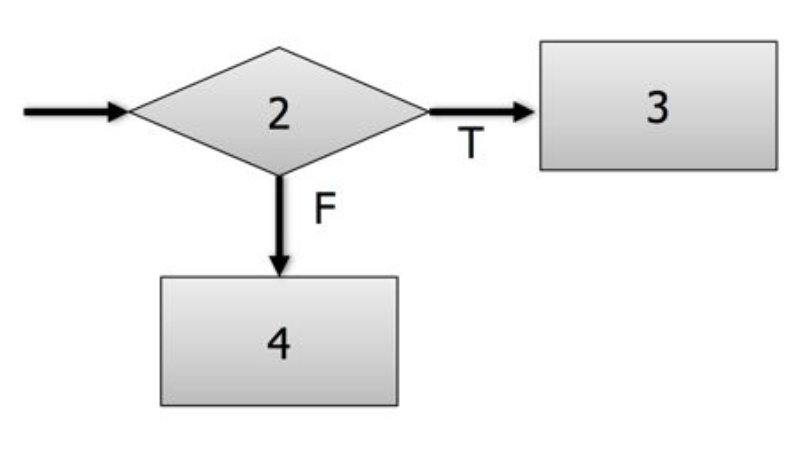

We will now use the test all paths strategy to test

Paycheck.calculateRegularPay(). The control flow diagram for

Paycheck.calculateRegularPay() is shown in Figure 11.

control-flow-calculateRegularPay.png

The cyclomatic complexity of Paycheck.calculateRegularPay() is 1 diamond + 1 = 2. This implies that there are as many as 2 valid paths through

the method. The possible paths are:

- 2-3

- 2-4

The tests shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7 cover the two valid paths for

the Paycheck.calculateRegularPay() method. Identifying the basis set of

tests for a method can help identify requirements and equivalence class

tests for a method. However, be careful about only considering valid

paths in your code! If your code is missing functionality, you will not

write tests for that. You should always think about requirements and

equivalence classes when writing unit tests.